Too many trips to the loo?

Author: Carolyne Horner

Publication Date: 11 February 2022

Ever wondered what happens to a clinical sample once it heads to the laboratory for diagnosis? Let’s start with the diagnosis of a ‘tummy bug’. Read on to find out what happens once you’ve captured some poo in a specimen pot!

Tummy troubles

Tummy bugs are common and typically present as sudden-onset diarrhoea and/or vomiting, but you may have other non-specific symptoms, such as abdominal pain/cramps, nausea, loss of appetite, fever and weight loss (if prolonged).

Tummy bugs (aka gastroenteritis or D&V (diarrhoea and vomiting) are associated with contaminated food or water, outdoor activities, such as barbeques or camping, and certainly with poor hand hygiene.

For most people, the infection doesn’t last long (<7 days) and resolves on its own without the need to visit a GP. This situation may be different for immunocompromised patient groups, including those at the extremes of age, who are at risk of prolonged or persistent infection.

More than a minor inconvenience

| Bacteria | Aeromonas |

| Campylobacter* | |

| Clostridium perfringens* | |

| E. coli O157* | |

| Plesiomonas shigelloides | |

| Salmonella* | |

| Shigella* | |

| Vibrio cholerae* | |

| Yersinia | |

| Viruses | Adenovirus 40 & 41 |

| Astrovirus | |

| Norovirus | |

| Rotavirus A & C | |

| Sapovirus | |

| Parasites | Cryptosporidium parvum* |

| Giardia lamblia* | |

| Entamoeba histolytica* |

There are many different types of tummy bug, including viruses, bacteria, and parasites (Box 1). These bugs (also known as microbes or pathogens) are highly infectious, spread easily, can cause serious illness, and may be associated with outbreaks. As such, gastrointestinal infections pose a risk to human health and are required by law to be reported to public health authorities.

There are around 17 million cases of gastrointestinal infection every year in the UK, which come with a hefty price tag in terms of social and economic costs. The Food Standards Agency estimated that in a single year (2018) foodborne disease cost UK society approximately £9.1bn, with most of this (£7.1bn) calculated to represent the human cost of pain, grief & suffering.

First things first

So, what happens if you do need to send a poo sample to the lab?

With so many different causes of gastroenteritis, it is not practical for the lab to test your sample for every possible pathogen. This is where a thorough clinical history and careful test selection comes in.

Certain activities and geographical locations provide clues as to the most likely cause of your illness. Your healthcare provider will want to know what you have eaten during the past week or so, details of any recent overseas travel, contact with animals, exposure to recreational or untreated water sources, hospital admission, and any antibiotic use.

Steps to a correct diagnosis

Based on this valuable information, diagnostic flowcharts are used to guide the most appropriate testing when your sample arrives in the laboratory.

Broadly speaking, there are three ways that your tummy bug will be diagnosed:

1) using a microscope to look directly at a tiny sample of poo

2) growing pathogenic (disease-causing) bacteria present in the poo

3) amplifying molecules from microbes

It is not routine practice to test a sample of vomit but it may be done for virus detection in certain instances when no poo sample is available, such as during a norovirus outbreak on a cruise ship.

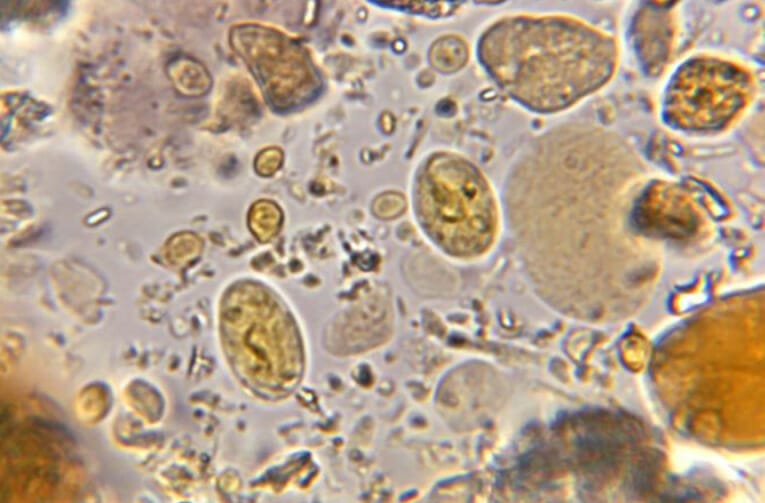

Parasite or pollen grain?

The microscope is used for detection of faecal parasites, such as Cryptosporidium and Giardia.

Rather than search for the actual parasite, which are usually fragile and like the safety of a nice warm body in which to multiply, biomedical scientists look down a microscope for ova and cysts. These forms are tougher than the parasites themselves, are able to survive in food and water, and survive ingestion and excretion from the body. Ova and cysts have characteristics specific for different parasites.

Image 1 shows an example of a wet mount preparation (a microscope slide with a tiny amount of your poo sample, plus a drop of saline under a cover slip) in which you can see the many different shapes and sizes of particles in a poo sample. Can you spot which are the parasite cysts?

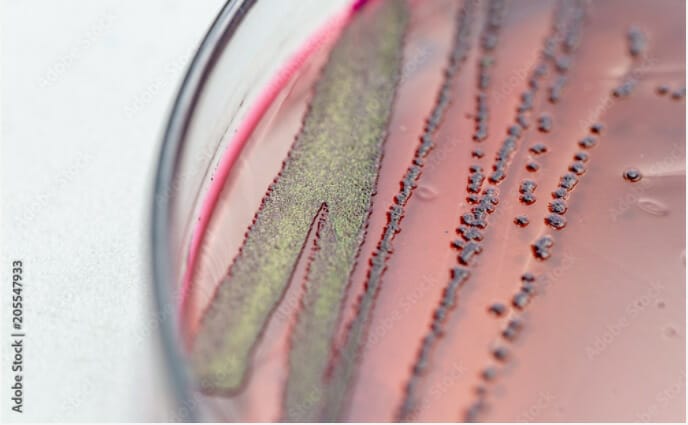

Friend or foe?

Looking for bacterial cells in a poo sample is not a sensible approach! Instead, a small amount of the poo sample is added to the surface of different agar plates. Selective culture is needed to encourage the pathogenic bacteria to grow and be identified from the background of other bacteria present in the gut (Image 2).

Once a bacterial colony has grown on an agar plate, the biomedical scientists in the lab need to identify the bacteria. One very quick way to do this is by using matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionisation time-of-flight mass spectrometry, or MALDI ToF for short! A tiny amount of the bacterial colony is transferred to a metal plate, the plate is put into the MALDI and zapped with a laser. As the zapped molecules are scattered, they create a particular spectrum of peaks that may be compared with an existing database and hey presto, the most likely bacterial match is reported.

For those labs that don’t have access to this piece of equipment, pathogenic bacteria from a poo sample are identified using a combination of methods, such as clues from the conditions in which the bacteria grow, how the colonies look when they have grown (colony morphology), and biochemical reactions.

Detection of bacterial toxins can also be used to diagnose infection and this is particularly important for the diagnosis of CDIFF (Clostridioides difficile) infection.

What about viral gastroenteritis?

Viruses are tiny compared with parasite ova and cysts and bacterial cells and cannot even be seen using a regular microscope. Viruses are not routinely grown in the lab either. Instead, the lab uses ‘molecular’ methods to detect the presence of viruses in a poo sample.

Here comes the science bit!

One commonly used molecular method is PCR, which stands for polymerase chain reaction. Your poo sample is treated with chemicals that strip out certain molecules and remove everything else. A clear liquid remains that contains the DNA (or RNA) of cells. This liquid is mixed with other ingredients, including primers attached to fluorescent probes that recognise DNA sequences specific to certain pathogens. During a process of heating and cooling on a ‘PCR machine’, the molecules of DNA are replicated over and over again. As replication occurs the amount of fluorescent dye is amplified and a signal is detected; this indicates which virus is present according to the specific DNA sequence.

Molecular methods are advantageous because they can look for the target sequences of more than one pathogen simultaneously, which is quicker than looking for microbes one type at a time.

Reducing needles in haystacks

It doesn’t take too much imagination to work out that looking for parasitic ova and cysts in a poo sample is rather like looking for a needle in a haystack. While growing bacteria is not difficult, culture can be slow (at least overnight) with identification and additional tests potentially taking another 2-3 days to complete. Molecular detection is a very sensitive method but may also detect dead pathogens, which is not so useful.

So, what other tools are available to the laboratory to aid diagnosis of your tummy bug?

Commercial kits can be used to detect pathogens directly from your poo sample. These kits are useful for detection of faecal parasites (saving a lot of time looking down a microscope) and bacteria that can be tricky to grow, such as Campylobacter. These tests can be added alongside the existing diagnostic procedures in the lab and potentially decrease the time taken to report your result.

A pathogen is announced

When a pathogen is detected and identified from your poo sample, the result will be shared with your healthcare provider and possibly with colleagues in public health.

Given the impact of gastroenteritis on the social and economic aspects, it is very important to minimise the spread of gastrointestinal infections. Colleagues in public health aim to determine the source of your infection and find out how many other people may be affected.

Laboratory says “No pathogen detected”

What happens when no pathogen is detected in your poo sample? A negative result will be reported to your healthcare provider and if you are still living with symptoms, you may need further investigations to determine the cause of your diarrhoea.

What about antibiotics?

In the majority of cases, antibiotics are not needed to treat your tummy bug (either because it is caused by a virus or because the infection has got better) and, in some cases, could make the condition worse. For certain patients, antibiotic treatment may be of benefit and the lab will advise which is the best antibiotic to use.

Antibiotic resistance among bacteria causing gastroenteritis is a concern. Strains of Campylobacter, Shigella and Salmonella that are resistant to multiple antibiotics are becoming more common and increasingly difficult to treat.

The end

I hope this highly abbreviated journey of a poo sample in the microbiology laboratory has given you some idea of the investigative work that goes on to identify your ‘tummy bug’?

Why not get in touch with Una and let us know what other sample types you would like to join on a journey in the microbiology lab.